This report documents the testimonies of Iraqi women who lost their children during the past seven years and do not know their fate until now. In this report, we interviewed Iraqi women in Nineveh and Anbar governorates, and we conveyed their testimonies as they were. The report also includes an approximate number of families who reported missing relatives during the past six years, and what procedures have been followed by Iraqi governments in this file.

The Iraqi Observatory for Human Rights on August 20 stated that the dossier of the forcibly disappeared persons in Iraq has fallen into oblivion. The Observatory added that the missing persons have become merely numbers cited in events and by media outlets, while no tangible measures are being adopted to uncover their fate.

The efforts of the successive Iraqi governments to address the dilemma of forced disappearances are unclear and may even be non-existent. Moreover, the further growing sense of desperation among the families of the forcibly disappeared and missing persons is an alarming indication of the loss of hope in uncovering the fate of these people.

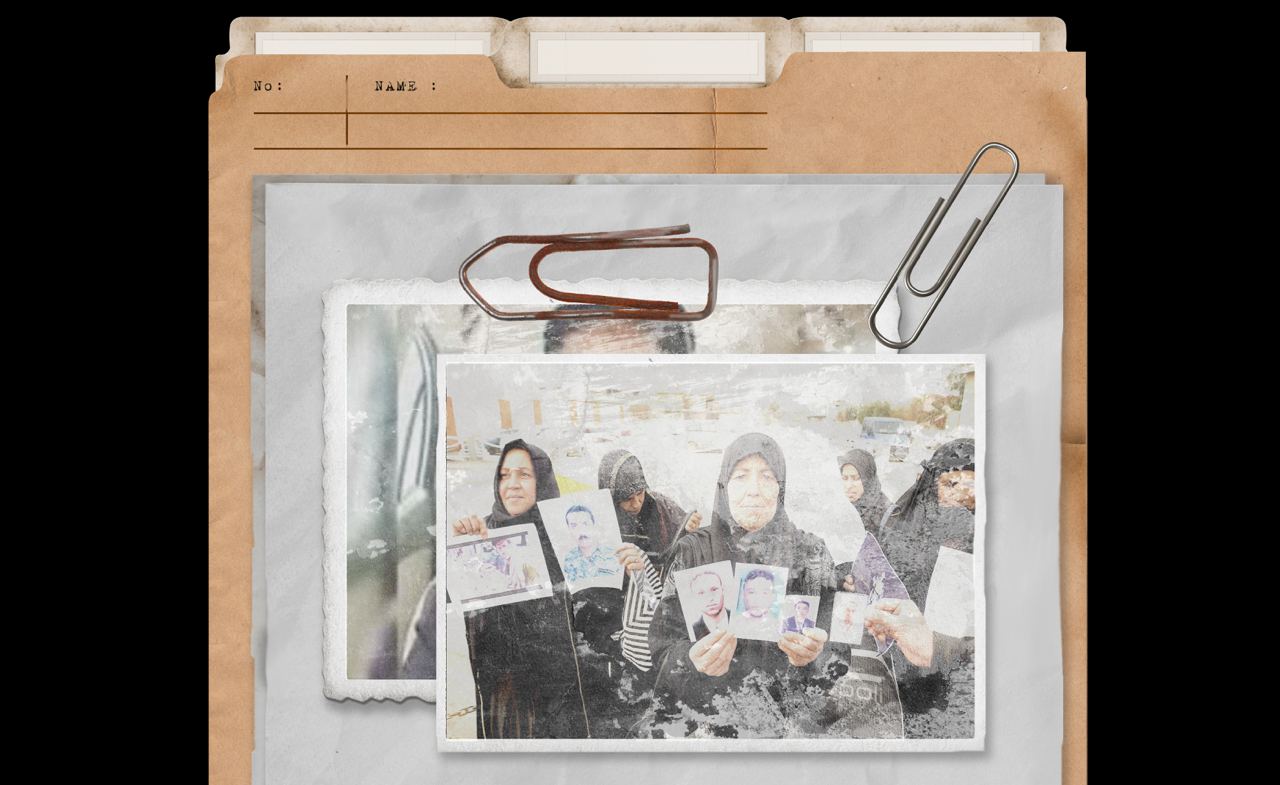

The Iraqi Observatory for Human Rights has spoken to a group of families from the governorates of Anbar, Nineveh, and Salah Al-Din, whose kin have gone missing. All the families highlighted the lack of efforts to address the dilemma of those who were forcibly disappeared or lost during the military operations to liberate Iraqi territories from the grip of the Islamic State group (IS), otherwise known as Daesh. These families further asserted a lack of information provided to the families about the fate of their kin. As a result, helplessness has taken over many of these families, especially as the 10th anniversary of the disappearance of their children is nearing.

Um Muthanna is an Iraqi woman in her 60s who lives in the region of Al-Saqlawiyah in Iraq’s western governorate of Anbar.

Reports indicate that more than 600 persons have gone missing from Saqlawiyah since 2016. However, the families from this region assert that the actual number of missing persons exceeds 700.

The Iraqi Observatory for Human Rights visited Um Muthanna in her Saqlawiyah home, where she stated: “On June 3, 2016, we left Saqlawiyah and headed towards [the territories controlled by] the Iraqi army. Before we knew it, rockets and shelling were being fired all around. We were received by the Iraqi army, the Federal Police, the Popular Mobilization Units, and men with green turbans wrapped around their heads. They took the men and told us they would return them in one hour after verifying their names/identities. However, eight years later, the men are yet to return.” She further noted that “some prisoners who were released told us that they saw our children in secret prisons.”

Recounting how the Iraqi security forces received and welcomed her and her two sons when they left Saqlawiyah, Um Muthanna stated: “They told us we are here to liberate you. They took my sons Ahmad and Muthanna. I am unaware of their whereabouts until now. Where is the government in all of this?”

Overwhelmed by her pain, the elderly woman cried, “We were held hostage in our homes when [IS] Daesh was in control, and now we are stuck between the heavens and the earth. We have no information about our children’s fate.” Um Muthanna elaborated that the Iraqi security forces said “they would verify the men’s names/identities. Is it reasonable to believe that all of the 750 [missing] men belong to [IS] Daesh?”

Marking the International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances on August 30, 2022, the Iraqi Observatory for Human Rights issued a report documenting the cases of forcibly disappeared and missing persons in Iraq. The report entailed testimonies of the relatives of those persons. Some 11,000 families have reported that their kin had vanished in the years stretching from 2017 to 2021.

Um Ahmad is a woman in her 70s from Nineveh governorate’s capital city of Mosul.

Speaking to the Iraqi Observatory for Human Rights, Um Ahmad recounted how her son disappeared in 2017 and how his whereabouts are still unknown until today. Um Ahmad stated: “During the Mosul liberation operations, the Iraqi security forces arrested my son Ahmad Hashem Sultan in the region of Wadi Hajar on January 13, 2017. We have not received any information about him since. We hear some news about him every now and then, stories that he is still alive, and we believe he is. We call on the Iraqi government to return him to us. We have endured a lot, and we want our children back.”

Iraq has been the scene of forced disappearances for more than five decades. However, for the past two decades, this issue has turned into a phenomenon with thousands disappearing. Although all the consecutive Iraqi governments have recognized this tragedy, none have taken adequate measures to uncover the fate of the disappeared and the missing.

Mustafa Saadoon is the head of the Iraqi Observatory for Human Rights.

Commenting on this issue, Saadoon stated that “the dossier of the forcibly disappeared persons and the missing cannot be reduced into a tally and an occasion that is marked and then forgotten. The consecutive Iraqi governments have not taken any tangible steps to reveal the fate of the forcibly disappeared and the missing persons. Instead, these governments resorted to establishing probe committees that are yet to present the public with any facts.”

Saadoon further noted that while “these committees have indeed reached some conclusions and facts, the results [of their probes] were not declared publicly for political reasons. All of this while the families of the forcibly disappeared and the missing persons’ sense of helplessness grows, and their pains and suffering deepen. These families ought not to lose hope. They should continue to demand that the fate of their missing kin be revealed.”

In 2010, Iraq ratified the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance and ought to commit to legislating a law with articles that conform with the Convention. However, despite lawmakers being elected to four four-year terms since, the Iraqi parliaments are yet to succeed in legislating any law relating to enforced disappearance.

A draft of the enforced disappearance law was introduced years ago, but it never saw the light, nor was it included in the Iraqi parliament’s legislation process. In 2019, the Iraqi Observatory for Human Rights participated in the discussion of a draft law relating to enforced disappearances. The discussion was held under the auspices of the Iraqi High Commission for Human Rights and saw the participation of the United Nations (UN) and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). However, working on the draft has stopped since.

Um Uday is a woman in her 70s from the region of Saqlawiyah in the Anbar governorate.

In Saqlawiyah, Um Uday is dubbed as the “mother of nine” in reference to the nine children she has lost. Speaking to the Iraqi Observatory for Human Rights about her loss, Um Uday stated: “During the Saqlawiyah liberation operations (June 2, 2016), at around eight o’clock at night, we escaped from our homes towards the posts held by the Iraqi security forces. When we reached their positions, some security members separated the men from the women.”

Um Uday asked why men were being taken to be told: “We will run a security check to verify their names/identities and will return them to you, but they never came back.” The elderly woman adds, “I lost nine of my children. Uday (1981), Luay (1983), Abd Al-Sattar (1985), Bashar (1987), Jassem (1991), Mohammad (1993), Bilal (1994), Maysam (1996), and Ahmad (1998).”

With a heavy heart, Um Uday spoke about the pains of waiting for the return of her sons. She stated, “Seven of them are married and have children. I, their wives, and children await their return, and our hope in God is still strong. On the same day my sons disappeared, some 750 men from the Albu Akkash village in Saqlawiyah went missing. Until today, nobody knows what happened to them.”

Overwhelmed with pain, Um Uday added, “We await their return. We don’t want anything from anyone except that they bring back our kin. What fault did I do to deserve losing nine of my children? What fault did their wives and children do?”

The Iraqi Observatory for Human Rights urges the current Iraqi parliament to be aware of the significance of legislating a law relevant to the enforced disappearances dossier. Such a law should entail clear and systematic processes to uncover the fate of thousands of forcibly disappeared and missing persons. It should further include establishing an independent authority or body tasked with following up on this dossier. Local rights groups, the UN, and the ICRC should also be allowed to contribute to addressing this dossier and ensuring the highest level of transparency possible. Moreover, the outcomes concluded in this regard should be announced publicly.

Information obtained by the Iraqi Observatory for Human Rights indicates that some 12,000 Iraqi families have submitted reports of missing persons between 2017 and 2023. While this figure is very high, it does not represent the total number of forcibly disappeared and missing persons. Hundreds of families are weary of taking legal action to demand to know what happened to their kin. The families’ fear indeed represents a transition point from hope to hopelessness regarding uncovering the fate of the missing.

The Iraqi Observatory for Human Rights has been following up on the forcibly disappeared and missing persons dossier for nearly a decade. The Observatory also monitors the Iraqi governments’ negligence and de-prioritization of this dossier.

Therefore, the Iraqi Observatory for Human Rights asserts that the forcibly disappeared and missing persons should not be forgotten, and their cases should not be dismissed. Moreover, the Iraqi authorities should not overlook this sensitive matter. After all, the responsibility to address this dossier is, first and foremost, that of state institutions, which are obliged to uncover the fate of the disappeared persons no matter what outcomes they conclude. The Observatory asserts that political calculations should not be given preference over Iraq’s human rights situation.